Directions: Read this story. Then answer questions 8 through 14.

Drawing Horses

by Cerelle Woods

I’d give anything to draw horses the way Euphemia Tucker does. She draws them in the margins of spelling tests and on the back of her math homework. They’re always running wild and free, their manes swirling over the paper like clouds across the sky.

5 Euphemia’s horses look so real you can almost feel their breath on your face.

10 Luke Anderson, who sits next to me, says he can’t decide whether my horses look more like Great Danes or kitchen tables. He also calls me Messy. I prefer Marisa, which is my real name, to Missy, which is what everyone – except Luke – calls me. If I could draw like Euphemia, I’d sign all my pictures Marisa. Nobody messes with Euphemia’s name, not even Luke Anderson.

15 Today I sharpened my pencil and took a clean sheet of paper out of my desk. Then I closed my eyes and pictured one of Euphemia’s perfect horses rearing up and pawing the air with its sharp hooves. I could see it so clearly I was sure I’d be able to draw it this time.

20 I started with what I do best: a big, billowing mane. Next, I roughed in most of the body and drew a long tail streaming out behind. It really wasn’t turning out half bad until I got to the front-legs-pawing-the-air part, which looked more like two macaroni noodles with tiny marshmallows for hooves.

I tried again, but the hooves still didn’t seem right, and rather than doing them over and over, I erased them and went on to the head. That was when I really ran into trouble.

25 First I drew some great donkey ears, followed by sheep ears, pig ears, kangaroo ears … everything except horse ears. I erased again and again until I had rubbed a hole in the paper. That was when Luke Anderson poked his nose over my shoulder.

I scratched a big X through my earless, macaroni-legged horse, wadded it up into a little ball, and stuffed it under the lid of my desk.

30 I was still upset when I got off the school bus this afternoon. I walked past the neighbors’ horses standing in the field next to our house. They’ve been in that field for as long as I can remember. Their stingy manes never float into the sky. Their ragged old tails hang straight down to the ground, and I’ve never seen them run.

35 I brooded about it all through dinner. After I’d helped clear the dishes, I sat down with a stack of typing paper and a freshly sharpened pencil. Without Luke Anderson there to pester me, I hoped I’d have better luck. I practiced a few horses’ heads, trying to get the ears right. Nothing worked.

I tossed all the sketches into the trash and walked outside. The sun had just sunk below the horizon, feathering the whole sky with pink and orange wisps. Everything looked special in that light, even the scraggly horses next door.

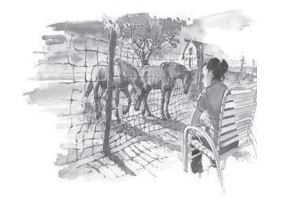

40 I dragged a lawn chair over to the fence and sat down to take a better look at them. They’d never be free spirits like Euphemia’s horses, but they did seem patient and strong. I noticed the curves of their muscles, the shadows on their faces, the shine along their backs. Their colors reminded me of dessert – rich chocolate, deep cinnamon, creamy caramel.

45 I was just sitting there, feeling kind of dazzled by the unexpected beauty of it all, when I remembered the big box of pastels my grandmother had sent.

50 An idea began to take shape in my mind, and just then the cinnamon horse turned its head toward me and nodded three times. It was like a sign.

I hurried into the house, grabbed the pastels and some paper, and raced for the door.

I choose a deep brown, pulling it across my paper in the shape of the chocolate horse. It comes out right the first time, even the legs and ears! Drawing horses is easier when they’re right in front of you, and I’ll say this for the ones next door – they hold their poses.

55 The sky is turning out just as I’d hoped, too; all the pinks and reds blending together like a strawberry parfait, and I love the way the caramel horse’s mane is blowing, just barely, in the wind.

It doesn’t look exactly like one of Euphemia’s horses, of course. But I already know that when this drawing is finished, I’ll be signing it Marisa.

8. In line 3, what does the simile “like clouds across the sky” help the reader understand about the horses in Euphemia’s sketches?

A. They are drawn sloppily.

B. They look like they are in motion.

C. They are getting tangled up with each other.

D. They look like they are trotting through the fog.

9. How do lines 14 through 16 contribute to the development of the plot?

A. They establish Marisa’s problem.

B. They emphasize Marisa’s hopefulness.

C. They contrast Marisa’s artistic abilities with Euphemia’s

D. They illustrate Marisa’s determination to not let Luke bother her.

10. Which phrase best conveys the tone in lines 1 through 30?

A. “They’re always running wild and free…” (lines 2 and 3)

B. “He also calls me Messy.” (lines 8 and 9)

C. “Next I roughed in most of the body…” (lines 17 and 18)

D. “I scratched a big X through my earless, macaroni-legged horse,…” (line 26)

11. Read this sentence line 32

I brooded about it all through dinner.

What effect does the word “brooded” have in the story?

A. It shows Marisa’s anxiety about her abilities.

B. It reveals Marisa’s motives for drawing.

C. It emphasizes how Marisa is growing as a character.

D. It indicates Marisa has a major decision to make.

12. How do lines 36 through 38 help convey the theme of the story?

A. They show that some situations take time to change.

B. They prove that practice can help natural talents to develop.

C. They suggest that inspiration may come in unexpected ways.

D. They demonstrate that new ideas will eventually be accepted.

13. Which sentence best explains why Marisa’s final horse drawing was different than her first tries?

A. “Everything looked special in that light, even the scraggly horses next door.”

B. “I noticed the curves of their muscles, the shadows on their faces, the shine along their backs.” (lines 42 through 44)

C. “An idea began to take shape in my mind, and just then the cinnamon horse turned its head toward me and nodded three times.” (lines 49 and 50)

D. “I choose a deep brown, pulling it across my paper in the shape of the chocolate horse.” (line 52)

14. How does Marisa change while watching her neighbors’ horses?

A. She realizes that Euphemia’s horses do not look realistic, so she decides to try to draw better pictures than her friend.

B. She decides to try a different way of drawing and is proud of her work.

C. She realizes she can never be an artist like Euphemia but wants to draw like her anyway.

D. She finally learns that drawing horses is easier with proper lighting and art supplies.

Directions: Read this story. Then answer questions 15 through 21.

Excerpt from The Black Pearl

by Scott O’Dell

I had put the seventh pearl on the scales and was carefully setting the small copper weights to make them come to a proper balance when I heard my father’s steps outside the office. My hand shook at the sound and one of the weights slipped from my fingers. A moment later the heavy iron door swung open.

5 My father was a tall man with skin turned a deep bronze color from the glare of the sea. He was very strong. Once I saw him take two men who were fighting and grasp them by the backs of their necks and lift them off the ground and bump their heads together.

He came across the room to where I sat at the desk on my high stool and glanced at the ledger.

10 “You work with much rapidity,” he said. “Six pearls weighed and valued since I left this morning.” He wiped his hands on the tail of his shirt and took a pearl from the tray. “For this one,” he said, “what is your notation?”

“Round. Fair. Weight 3.5 carats,” I answered.

He rolled the pearl around in the palm of his hand and then held it to the light.

15 “You call this one only fair?” he asked. “It is a gem for the king.”

“For a poor king,” I said. After four months of working with my father, I had learned to speak my mind. “If you hold it closer to the light, you will see that it has a flaw, a muddy streak, about midway through.”

20 He turned the pearl in his hand. “With a little care the flaw can be peeled away,” he said.

“That, sir, I doubt.”

My father smiled and placed the pearl back in the tray. “I doubt it also,” he said and gave me a heavy pat on the back. “You are learning fast, Ramon. Soon you will know more than I do.”

25 I took a long breath. This was not a good beginning for the request I wanted to make. It was not good at all, yet I must speak now before my father left. In less than an hour, the tide would turn and the fleet sail from the harbor.

“Sir,” I began, “for a long time you have promised me that when I was sixteen I could go with you and learn how to dive for pearls. I would like to go today.”

30 My father did not reply. He strode to the slit in the wall and peered out. From a shelf, he took a spyglass and held it to one eye. He then put the spyglass down and cupped his hands and shouted through the slit.

“You, Ovando, leaning against the cask, send work to Martin, who leans against the tiller of the Santa Teresa, that there is much work to do and little time in which to do it.”

35 My father waited, watching through the slit until his message was sent forward by Ovando.

“If you go with the fleet,” he said, “then all the male members of the Salazar family will be on the sea at once. What happens if a storm comes up and drowns both of us? I will tell you. It is the end of Salazar and Son. It is the end of everything I have worked for.”

40 “The sea is calm, sir,” I answered.

“These words prove you a true landsman. The sea is calm today, but what of tomorrow? Tomorrow it may stand on end under the lash of a chubasco.”1

“It is still a week or two before the big wind comes.”

45 “What of the sharks? What of the devilfish that can wring your neck as if it were the neck of a chicken? And the giant mantas by the dozens, all of them the size of one of our boats and twice as heavy? Tell me, what do you do with these?”

“I have the knife that grandfather gave me.”

My father laughed and the sound bounded through the room like the roar of a bull.

50 “Is it a very sharp knife?” he asked scornfully.

“Yes, sir.”

“Then with much luck, you might cut off one of the eight arms of the devilfish, just before the other seven wraps around you and squeeze out your tongue and your life.”

I took another breath and brought forth my best argument.

55 “If you allow me to go, sir, I shall stay on deck while the others dive. I shall be the one who pulls up the basket and minds the ropes.”

I watched my father’s face and saw that it had begun to soften.

60 “I can take the place of Goleta,” I said quickly, to follow up the advantage I had gained. “There is an apology to make, sir. At noon Goleta’s wife came to say that her husband is sick and cannot sail. I forgot to tell you.”

1 chubasco: a strong storm

My father walked to the iron door and opened it. He looked at the sky and at the glossy leaves of the laurel trees that hung quiet on their branches. He closed the door and put the tray of pearls in the safe and turned the bolt.

“Come, he said.

15. Read line 15 of the story.

“You call this one only fair?” he asked. “It is a gem for the king.”

What does this line suggest about the father?

A. He has not looked at the pearl as closely as Ramon has.

B. He does not think that Ramon is correct about the pearl.

C. He is testing Ramon’s confidence in judging the pearl’s value.

D. He is teaching Ramon about the pearl’s quality.

16. Which detail from the story best supports the idea that Ramon is becoming an expert at judging peals?

A. “For this one,’ he said, ‘what is your notation?” (lines 11 and 12)

B. “For a poor king,’ I said.” (line 16)

C. “‘With a little care the flaw can be peeled away,’ he said.” (lines 19 and 20)

D. “I would like to go today.” (line 29)

17. Why is the father reluctant to bring Ramon on a pearl-diving trip?

A. He is concerned about Ramon’s safety.

B. He needs Ramon to evaluate more pearls.

C. He thinks Ramon is still too young to sail.

D. He is unsure Ramon is ready to dive.

18. In line 55, why does Ramon suggest that he will “stay on deck while the others dive”?

A. His father needs him to help with other jobs on the boat.

B. He realizes that his father will never actually let him go.

C. His father has convinced him that it is too dangerous.

D. He is trying to gradually change his father’s mind.

19. How does line 57 best contribute to the development of the story?

A. by signaling a turning point

B. by providing a solution to the problem

C. by comparing the characters’ actions

D. by introducing a new conflict

20. How does the father change during the story?

A. He becomes concerned about a diver’s health.

B. He begins to acknowledge Ramon’s maturity.

C. He becomes frustrated by Ramon’s persistence.

D. He stops worrying about his family business.

21. The author develops Ramon’s point of view in the story mostly by

A. describing Ramon’s fear of pearl diving

B. including Ramon’s analysis of the pearl

C. describing how Ramon feels about his father

D. including dialogue between Ramon and his father

Directions: Read this article. Then answer questions 29 through 35.

Move Over, Spider-Man-Here’s Spider-Goat!

by Joli Allen

Making silk threads isn’t just for spiders anymore. A special type of goat is doing it, too. Nubian goats look and act like any other playful, floppy-eared goats. But when they aren’t playing, these goats are busy making spider silk.

5 Spider silk is absolutely amazing. It’s five times stronger than steel, but it’s also very light and flexible. Because of this, scientists plan to use it to make some totally cool things! Imagine clothing that’s as light as a cobweb, yet won’t tear, or fishing line and tennis racket strings that won’t break. Doctors might be able to use spider silk for making tiny stitches in delicate eye surgery, but it could also be strong and flexible enough to replace some worn-out parts of the human body. The silk also could be used to build

10 airplanes, buildings, and bridges, as well as create a tough coating for space stations. Because of all these possibilities, scientists have been searching for ways to make spider silk in huge quantities, and they have finally found the answer: Nubian goats!

Scientists have studied spider silk for years. They tried to raise spiders on spider farms to collect silk from them, but the spiders didn’t enjoy living so close to one another.

15 Spiders like their own space, and when they don’t get it…well… they make space by eating their neighbors!

Goats, the scientist discovered, are much friendlier than spiders and are also easier to work with. Because they’re bigger, a few goats can produce more silk than a roomful of spiders. The scientists chose Nubian goats for this job because they make milk at a

20 younger age than many other goats. So, the Nubian goats will make spider silk sooner and for longer periods of time.

But how do the goats actually make the spider silk? That’s what scientist Jeffrey Turner wanted to figure out when he taught animal science at McGill University in Montreal. He noticed that the body parts of spiders that make silk and the parts of goats that make milk

25 are very much alike. Because of this, he figured that goats might be able to make spider silk. The idea excited him, and he started his own company in 1993 to do more research on how goats could do what spiders have been doing for years.

Eventually, Turner and his fellow scientists found a way to place spider genes in goats so that the genes fit nicely, like a guest in a comfortable hotel. Every living animal,

30 including humans, has a set of genes inside of it that tells its body what to do. These genes are very, very tiny, but they hold lots of information on how to build parts of the body. A spider’s genes contain instructions for making spider silk, and a goat’s genes contain instructions for making milk.

So by putting spider genes into goats, the goats then have the genes that tell their bodies how to make spider silk proteins.

35 Proteins are the body’s basic building blocks. Just as people have proteins in their bodies that make their hair, skin, and muscles, the goats now have special proteins for making spider silk. When the goats produce milk, the spider silk proteins are in it, but it looks just like regular milk. Scientists separate the proteins out of the milk by skimming off the fat and then sprinkling salt on it. The salt makes the spider silk proteins curdle into

40 small clumps. These clumps are scooped out, and water is added until the mixture has the thickness of maple syrup. This is spider silk, and it’s ready to be spun!

45 Next, the silk is taken to a spinning machine that copies the way spiders spin their silk. The secret to extra strong silk is in how the spiders spin it: they stretch the silk over and over again. The stretching makes all the protein building blocks line up, lock together, and form a strong but flexible band. When the giant spinning machine is finished, the silk threads are stronger than steel and as flexible as rubber… but they’re also thinner than a human hair.

50 Producing milk with spider proteins in it doesn’t hurt the goats. Scientists did years of research to make sure the goats would be safe and healthy. The milk that’s left after the spider proteins are removed can still be used – as fertilizer on fields that grow feed for the goats.

In 19998, Dr. Turner bought a farm in Canada for raising his spider-silk goats, and they still live there today. The one thousand goats that make spider silk are raised in a normal environment and are healthy, curious, and energetic – just like any other Nubian goats.

55 Their owner gives them lots of space to roam and play. The goats particularly enjoy rolling down the farm’s grassy hills, and they love listening to country music. Other music, such as rock music, has strange rhythms that make the goats jittery, but the steady beat of country music keeps them calm and happy. H’m…I wonder if they’d like the “Itsy Bitsy Spider” song.

29. In lines 4 through 12, the author explains why scientists are trying to find a way to produce spider silk using goats by showing

A. possible uses for spider silk

B. the popularity of spider silk

C. how easy spider silk is to use

D. how quickly spider silk can be developed

30. Which statement best explains the advantage of using goats rather than spiders for the production of silk?

A. Goats produce stronger silk than spiders do.

B. Scientists can insert genes into goats but not into spiders.

C. Spider proteins in goat milk can be spun into silk.

D. Goats are bigger than spiders and are much easier to raise.

31. What did Jeffrey Turner discover about using Nubian goats for possible silk production?

A. Nubian goats already make a similar substance.

B. Nubian goats have high amounts of protein in their milk.

C. Nubian goats and spiders both prefer living in large groups.

D. Nubian goats and spiders have body parts that are similar.

32. In the process described in lines 35 through 47, which step allows the threads to become strong enough for surgical procedures?

A. The silk proteins are turned into clumps.

B. The silk is stretched repeatedly.

C. Salt is added to the goat’s milk.

D. Water is added to thin the clumps.

33. Why are lines 55 through 59 important to the article?

A. They suggest that the goats are unusual.

B. They explain how the goats are kept busy.

C. They explain that the goats are treated well.

D. They suggest that the goats are like humans.

34. Which statement best expresses a central idea of the article?

A. Nubian goats produce better quality silk than spiders.

B. Spider silk is a complex substance that takes effort to make.

C. Nubian goats have been genetically altered to produce spider silk.

D. Spider silk contains proteins that are similar to proteins in other living things.

35. Which detail is the most important to include in a summary of the article?

A. Scientists have made an attempt to gather silk from spiders living on farms.

B. Spider silk has qualities that can be used in many products.

C. A scientist started a company to research goat silk.

D. Machines spin spider silk into thin threads.

Book 2

Directions: Read this story. Then answer questions 36 through 42

Nina has just received a low grade on a social studies test. Before she can figure out what to do, the bell rings and she heads to her art class.

Excerpt from Interference Powder

by Jean Hanff Korelitz

The art studio was at the end of the corridor. Its walls were splotched by years of flung paint, and pockmarked from thousands of thumbtacks. All sorts of stuff was pinned up, from kindergarten smudges to our own collage self-portraits, with papier-mache objects dropping down from the ceilings to sway over our heads. One of my own paintings hung on the wall between two of the windows, and I smiled when I saw it. It was a picture I was kind of proud of: a study of Isobel’s face, up close, her thin smile stretching across her face and her skin very white against a purple background. Isobel called this her vampiress portrait, which wasn’t exactly a compliment. Still, I knew she liked the picture and felt proud to see it up on the wall.

10 When we got to the art room, I was surprised that Mrs. Smith, our teacher, was absent and her place stood a tall woman with long hair in hundreds of little braids, some of them with beads and shells woven into their ends. The hair was mostly gray, but the woman’s face wasn’t really old. In fact, she looked around the same age as my mom. She grinned at us from the center of the room, with her hands thrust deep into the pockets of her big, faded apron, which she wore over jeans so worn they looked buttery-soft. In one ear she wore a long, dangly earring with a feather that brushed her shoulder. Nothing was in her other ear. Her fingers were bare, but her wrists clattered with little bracelets, silver and gold and every color. I stared at those bracelets. I had never seen anything like them.

20 Our class was bunched up at the door, uncertain about whether or not to enter, given that our art teacher wasn’t there; but this different person mentioned us inside, grinning all the while. “Come on!” she said gleefully. “Mrs. Smith is sick today, so I was called in. My name is Charlemagne.”

25 Charlemagne! Isobel and I exchanged a look. Only the week before, Isobel’s father had shown us a print of an old painting with a man in a chair. Four priests were standing over him, waving something that looked like palm fronds.

“Is he a saint?” Isobel had asked.

1 fronds: branches

Her dad had laughed. “He thought he was. But no. He’s King Charlemagne of France. Charles the Great! He made war on absolutely everybody.”

30 And now, here we were, only a week later, confronted with one of Charles the Great’s actual descendants, since what else could Ms. Charlemagne be? Imagine being descended from a medieval French king! How totally thrilling! Mom always told me that her great-great-great-uncle had invented the glue they use on the back of postage stamps, but that was nothing compared to being connected to ancient royalty.

35 Ms. Charlemagne began passing out paper as we drifted to the art tables. “I don’t have any special plan today,” she said. “I think we’ll just see where our creativity takes us. Let’s see what happens on the page. After all, that’s what artists do, isn’t it?”

Was it? I’d always thought they planned their paintings beforehand and then tried to make the picture on the canvas match the picture in their mind. That’s what I always did, anyway.

40 The kids around me were picking through the pencil and crayon bins, looking at one another with uncertain expressions. They were used to being told by Mrs. Smith with what the day’s subject was or how they were supposed to make their pictures.

“Let’s let the colors pick themselves!” Ms. Charlemagne chirped. “Let’s let the pictures tell us what they should look like! Let’s see what’s on your mind today!”

45 I looked down at my blank white sheet. I knew what was on my mind. My low 62 grade, my never-to-be-had singing lessons, my mom’s expression when she sees my test score tonight. I sighed and reached for a pencil. I began to draw my mother in our kitchen at home, her face pinched up in a frown. I drew her thin eyebrows and her eyes, with their pretty, curling eyelashes, looking down. I drew her hair falling forward a bit and one hand, the one that still wore my father’s wedding ring, on the table before her. Next to that hand I drew my test; and just to make myself feel even worse, I drew my ugly score-62-right there on the paper. For a long moment I glared at it, as if willing it to change.

55 Then it struck me! I could change that number, at least here if not in real life. I could turn my pencil over and rub those terrible numbers away, then write numbers in their place. I was the lord of my own picture, wasn’t I? I could give myself a 63 on my social studies test, or a 61, or…why not even a perfect 100?

36. How does Nina’s attitude toward Ms.Charlemagne change?

A. Nina becomes less interested after noticing Ms. Charlemagne’s bracelets.

B. Nina becomes more fascinated after learning Ms. Charlemagne’s name.

C. Nina becomes less surprised after hearing Ms. Charlemagne’s viewpoints.

D. Nina becomes more suspicious after hearing Ms. Charlemagne’s assignmennt.

37. How do lines 34 through 39 contribute to the development of the story?

A. by suggesting that Ms. Charlemagne is not qualified to teach art

B. by introducing Nina to a new way to think about art

C. by showing that Ms. Charlemagne does not understand how artists work

D. by describing the way Nina usually complets art assignments

38. Why does the author use the word “chirped” in line 43 of the story?

A. to reveal that Ms. Charlemagne has creative ideas

B. to imply that Ms. Charlemagne is new at teaching art

C. to demonstrate that Ms. Charlemagne has a cheerful outlook

D. to show that Ms. Charlemagne easily relates to the art students

39. Read this sentence from line 54.

I could change that number, at least here if not in real life.

How does this sentence best contribute to the development of the story?

A. by signaling a change in Nina’s thinking

B. by emphasizing the importance of the setting

C. by revealing Nina’s strong feelings

D. by suggesting a new plot development

40. Which quotation best supports a theme of the story?

A. “Still, I knew she liked the picture and felt proud to see it up on the wall.” (lines 8 and 9)

B. “I had never seen anything like them.” (line 18)

C. “Imagine being descended from a medieval French king!” (lines 30 and 31)

D. “I was the lord of my own picture, wasn’t I?” (line 56)

41. Based on details in the story, what can readers conclude about Ms. Charlemagne?

A. She is a respected artist.

B. She has a famous relative.

C. She has a unique personality.

D. She is a popular substitute teacher.

42. How do the details in the story help develop a theme?

A. Nina’s thoughts about her mother help develop the theme that being hones will make you feel better.

B. Nina’s interaction with Isobel helps develop the theme that experiencing a new situation is easier with a friend.

C. Nina’s drawing helps develop the theme that expressing yourself can help you work through your struggles.

D. Nina’s description of Ms. Charlemagne helps develop the theme that judging others by their appearance is not a good idea.